Mobster film aficionados and Civilization fans alike should be clocking the development of Empire of Sin, a gangster era strategy game set in 1920s Chicago. Carrying a unique development pedigree under Romero Games with a distinctive alliance with publisher Paradox Interactive, the upcoming game is shaping up to be the kind of intricate and forward-thinking strategy project that, as its team will humbly admit, isn’t exactly like any other game on the shelf.

Director Brenda Romero musters the most name recognition among Empire of Sin’s creative roster, but speaking to the development leads alongside her describes a kind of dream-team dynamic. It would be all but required for the ambitions of the game, which combine several different gameplay pillars and threads with turn-based combat and a real-time component that, as we discuss below, is pushing against the grain.

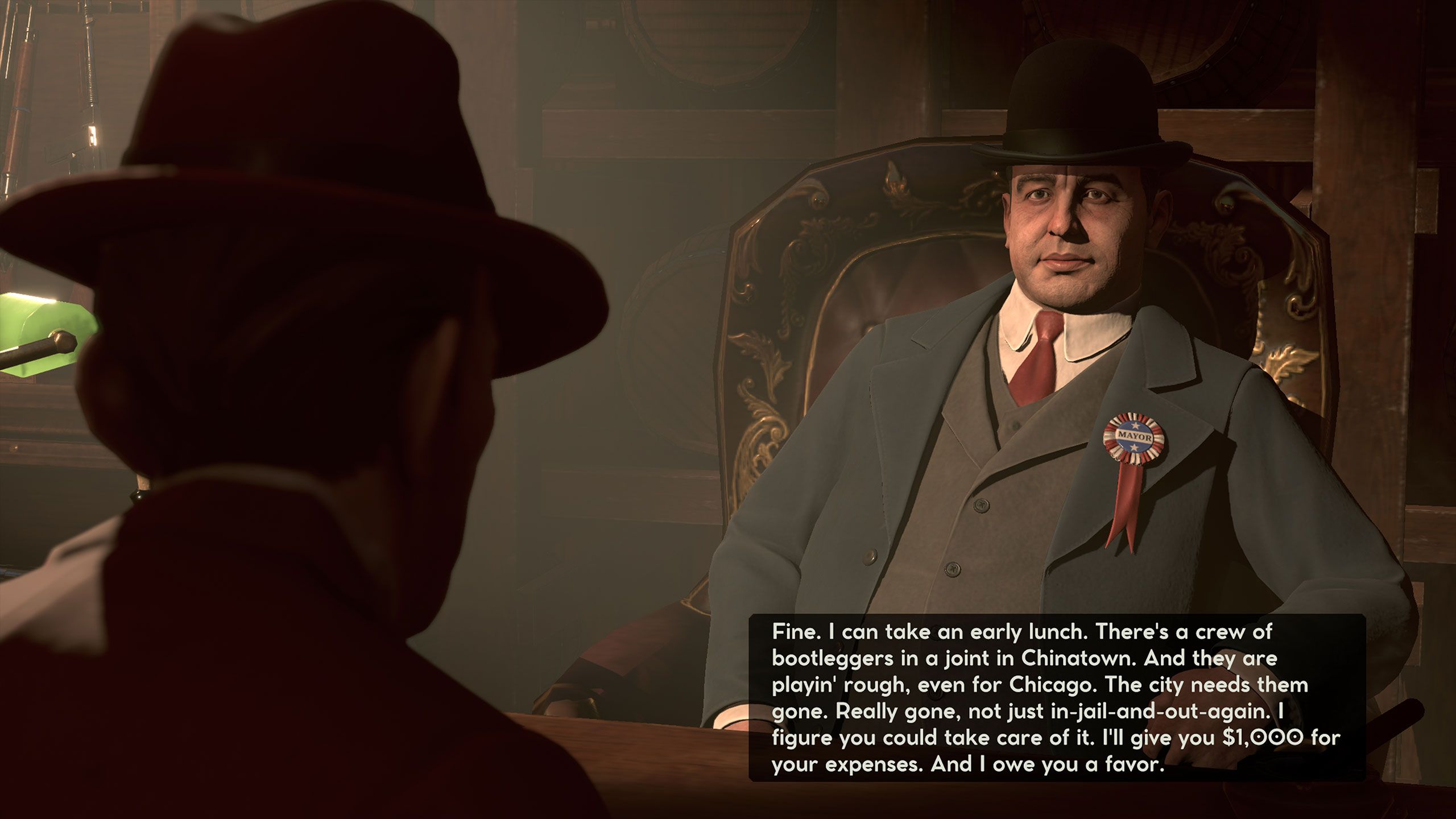

Screen Rant was afforded the opportunity to speak with Brenda Romero, Lead Narrative Designer Katie Gardner, Senior Game Designer Chris King, and Principal Combat Designer Ian O’Neill about the seedy and strategic bathtub gin world of Empire of Sin. The latter is cutting his professional teeth with this project, in addition to debuting his acting chops as the voice of Frankie Donovan, the Irish mob boss we took for a spin in our Empire of Sin preview feature.

I remember how your press introduction before the demo described this was a passion project that had been kicking around for a while. Where did Empire of Sin emerge from? Even the game’s theme is rare all on its own, as we never see a lot of games taking place within this time period.

Brenda Romero: So, I have been trying to make a game set in this time period for probably 20 years. And if you could just imagine throwing everything you know about it, and sticking different magnets in there to see what is sticking to those ideas. Nothing ever really gelled to the point that, like, I couldn’t wait to play it…until Empire of Sin. That idea gelled.

It actually goes back to when I was ten years old. I grew up in Northern New York on the Canadian border. There’s a bar in my hometown called The Place. And that bar - it’s still open in fact - that bar apparently never closed during Prohibition. So, when I was young, it was the oldest continuously operating bar in the US. Now, I’m sure some other bar didn’t close, but that’s what I knew about The Place.

So, like a curious ten-year-old, I asked my mother. And my mother’s a lot like Dean O’Banion, right? She’s pretty devout. And I asked her because, there’s two key things about The Place: it’s on the main street in town and it has giant picture windows. So, there’s zero chance that people didn’t know about this. I asked my mother, “How could this have never shut? The cops can see it, why wouldn’t they just go, excuse me, you need to close down?” And my mother, not wanting to say, not wanting to like, let me know that cops turn a blind eye and could be bribed, not wanting to let me know about this grey area at ten, just kept not-answering the question.

So, it inadvertently spawned this love of criminal empires. I remember going to the library and looking stuff up, and I’ve just always been fascinated with that whole thing, and it just never went away, ever. So, then, eventually I got my answer. My grandfather walked alcohol across the border, because the Saint Lawrence river used to be rapids at the time, so you could just walk alcohol across from Canada. It was really, really common. I just became fascinated with it. If you’re really interested in something, you just do that [something], and if you’re a game designer, if you’re interested in something and you love games, you wanna play in that space.

So, eventually, a pitch came together. I got the roots of it five years ago, and it was not something that existed, and not something that I had ever played before. I pitched the game to Paradox, which was probably the most nervous 20 minutes of my life. I’m really comfortable speaking, but I knew, desperately, because it was a strategy game, I knew desperately that I wanted Paradox to have this game. If anybody said, “What shouldn’t you do?” I would say, “Well, don’t pitch an idea that is specifically for that company. Because if that company doesn’t take it, what are you gonna do?” But I didn’t follow that advice.

Then we started making it. But the cool thing is having all the team there and a whiteboard leaning against the desk, and saying, “Okay, you’re in Chicago.” [There weren't] many of us, 8 or 10. “You’re a boss, you’re in Chicago, what do you wanna do?” And that’s it. That’s where the verbs of the game come from. It’s really built by a team. I know that sounds like a game developer greeting card or motivational poster, but it really, seriously is.

Ian O’Neill: The HR slogan: “Our games are built by the team.”

I was turned onto your work many years ago. I knew it - though not by the moniker of “The Mechanic is the Message” - but I remember first reading about Train, and it blew my mind. And then the other projects that you’ve done under that banner. I can’t help but look at this game with thoughts directed at those projects. I mean, maybe specifically about how there are secret things going on when you’re playing Empire of Sin. Some you’re fully aware of, some you’re only aware of when they interfere with an action, and some you’re not aware of at all. I was wondering how your work in "The Mechanic is the Message" may have influenced Empire of Sin.

Brenda Romero: It’s the same set of tools. You’re actually the only reporter who’s asked that. So, thanks, it’s an honor that you know about the board game work, I appreciate that.

Those games, I would say, really sharpened my ability or my passion for looking at something that’s historical, finding the systems that are in it, the core systems, the necessary systems. And then those things can sit on their own, and then you sort of see how the system is running. And that’s the same in any of those games. Then, how is the system running? And then the last question comes, which is, how do I put the player into that system? So, is the player, for instance, going to be a citizen living in that city? Is the player going to be a cop? Elliot Ness, say, trying to shut it down. Is the player going to be able to play both the cops and the gangsters? Who is the player?

That’s where you evolve from, “Who is the player?” to “Who do I want to be?” Well, I want to be a gangster. Okay, great, I want to be one of those bosses. Do I want to be one of those bosses who, we’re all badass, we’re all as powerful as each other? And I really loved the idea of that upside-down [status]. I’m actually nobody, right? I have zero notoriety. I am nobody, and I’ve got to build myself up from nothing along with everybody else. So, the other board games have their roots in historical simulation, and trying to figure out what are just the most raw elements of that that I want to grab.

I would not have seen the complex interdependencies of these systems – the RPG aspect, the sim aspect, the empire-building aspect – if it hadn’t had been for those games. Probably City Soleil being the biggest one. The rules are done for City Soleil, but I have to finish this game before I can build the set that is City Soleil, which is the game about day and night violence in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

I’m constantly thinking of Civilization while playing it, which also caused me to wonder if there were multiple methods available to reach an endgame state. Can all the bosses hold hands in peace and harmony and dance in a circle?

Brenda Romero: Dammit, Ian, I told you I wanted that feature! I told you I wanted the dance feature!

Chris King: We do have a canonical victory, which is essentially elimination, where you are the sole last man or woman standing in Chicago and you win the game. But, obviously, we have created a Chicago that is a sandbox, and if you want to get all the bosses in Chicago around a fireplace kumbaya-ing, if that’s what you want to do, then knock yourself out! It’s a Chicago where you can make what you want from it.

How long should one good playthrough of Empire of Sin take?

Chris King: I think the thing here is, it’s actually going to depend on the settings. You can actually choose the size and scope of your game, because you can actually choose the size and scope of your game. You can change the number of neighborhoods from Chicago from 3 to 10, the number of bosses which goes from 6 to 13, depending on, also, the size of the neighborhood. So, if you’re kind of going for a default game, which I think is 10 and 10, we reckon, I think, 15, 20 hours, minimum. And that also depends how ruthless you are. If you are really, really good, and can min-max, and can really take out bosses and safe houses, which I can’t do without cheating in the early game, I’m gonna confess (the console is your friend), then you might be able to do it quicker.

Brenda Romero: When I tend to play, my favorite way is 3 neighborhoods, 10 bosses, which results in, basically, chaos. Really, there’s a very short amount of time and people are constantly competing for resources. That game, I would say, is 10 or 15 hours. I tend not to follow the RPG path, which is the personal missions, the boss missions, and there’s a lot of really good work and interesting things that are in there. Katie and I were talking about the story of Maggie Dyer. You played Frankie, and Frankie’s story is quite rich, where he has to make some pretty significant choices. Depending on the extent of what you choose to do in the game, that will affect the length of the game, especially if you leverage those RPG elements.

Yeah, I think I played half the demo without even looking at my objectives, and then I was like, wow, there are all these missions here!

Brenda Romero: Some of those are there just for players who need direction. “Okay, I’m in Chicago, what am I supposed to do. Thank goodness, that’s there!” But there’s other things that’ll come up like, Katie, you can talk about how characters gain a certain level of loyalty.

Katie Gardner: Yeah. So there’s lots of different types of missions. Some you’ll find if you’re just walking around the city, you might see a yellow arrow come up like, oh, someone needs something over there. Some gangsters also have missions tied to them, and when you get to a certain amount of loyalty, then they’ll approach you and say, “Hey, I’ve got this thing going on, can you help me out?” And you can make a decision about how you want to help them, or if you want to help them.

And, of course, the bosses have their long sprawling missions tied to them. Everything that’s about the rewards for the missions kind of feeds back into the other layers of the game. It’s made to help you with your empire if you choose a certain path. You know, it’s kind of, oh, if you go down this way, it could help you with your faction rating with other bosses, this way might help you with your rackets, this way might help you with police. So, that’s how we designed the missions, with the other layers in mind.

Brenda Romero: It is not a linear narrative. In every play session, there’s so much stuff that you’ll never hit, that you will not do, because you didn’t satisfy whatever the writing teams’ weird set of circumstances were to launch a specific mission. But, because of that, when something happens, like when somebody’s in love with somebody else – this person has become something they wish they weren’t, as a result they want to know if you can help them out with it. Because they arise from your play and what you’ve done, it’s not like, “Oh, thanks for the mission.” You caused this, this happened. That set of circumstances may not happen in another playthrough.

Ian O’Neill: We were only saying this morning, in the last two weeks, that I haven’t had two games that were exactly the same. I hired different gangsters or I started in different neighborhoods, or I lost a gangster; permadeath is a very important aspect in Empire of Sin. So, if you lose one of your early gangsters, they’re gone. They’re not coming back, no ankh, no scroll of resurrection, they’re just gone for the rest of that game, and you’ve lost a powerful asset. So, it’s now down to you to try and make do with what’s left. But you also then lose any relationships that they had, any stories or missions that were attached to that character are gone as well.

Time is a funky concept in Empire of Sin, right? The world doesn’t move during combat, right?

Ian O’Neill: Time is paused when you’re in combat.

No offense to you all, but "normal" developers would not have made this game real-time. During my demo, I actually left my desk for a while, but I forgot to pause it, and when I came back I saw that chaos had occurred while I stepped away. I’m like, wow, all the wheels of this machine are constantly turning when you look away.

Brenda Romero: Yeah. And there are so many wheels.

Ian O’Neill: Here’s an example. We just got off a Twitch stream, and every week we will check the stability of the saves, and that means playing through the save from last week just to make sure we can play it on the next stream. So, I was looking around the map and I was full f—king sure that I knew where there was a stash, and I knew where it was, I marked it in my head. I knew I was gonna get this epic stash, get an epic weapon, and gear up to go and fight this safehouse. Then I was gonna go get a legendary stash, and I was hoping it would be a good chunk of cash. When I went to get it, it was f—king gone. One of the other faction AIs had already went and picked it up.

They’ll actually do that?

Ian O’Neill: They’ll go and pick up the stashes. They’ll go around the city and loot your stashes. In a normal RPG, your [loot drops] are there for you, but here they’re available to everybody.

Brenda Romero: I totally agree with you that having a single time sense would have been something normal people would have done. We wanted the experience of being a boss and walking around Chicago, though, and that didn’t include, “Ian, it’s your turn now, we’ll wait.” And it worked. It can be done, it’s just minding the time inside the systems, and like, how much time is a tick? How much time passes in a tick?

Chris King: The real time in the strategy layer is very good if you want to progress. So, for example, I want to wait a couple of weeks to get enough money to do something. In a turn-based environment, you’ve got to press next turn, next turn, next turn, whereas with a strategy environment I can wander Chicago looking for a legendary crate. So, it’s a very good way to effectively deal with strategic downtime.

Ian O’Neill: That’s also a really interesting part of our talents system for gangsters. So, your talents don’t unlock from experience or kills or points you acquire – they’re [based on] time, because you’re learning something new. You’re essentially saying to your hired gun, your demolitionist, your mob doctor, “I want you to learn a new trick, but it’s gonna take time.” And the more complex, the more badass the talent, the longer it takes. And that’s real time. So, while you’re flicking between fights, you’re delaying your talent-learning. At some point, you want to think to yourself, “Okay, I really want this talent, I’m gonna take a break and do something else for five minutes so I can unlock this talent.” It’s another choice you have to make.

Something else that came up while I was playing as Frankie was the traits system. I brained a bunch of people in combat and was told that I gained the “thirst for violence” trait.

Brenda Romero: All gangsters and bosses start with traits, a set of traits that they all have. There are their early childhood traits, and the traits they get and gather through their life experience before you meet them. That will be the same in every game. However, the things that they end up doing in the game, the people with whom they interact, the things that happen to them and the choices that you make can accrue traits to those characters.

Katie Gardner: If you keep executing people as a gangster, after a certain threshold, they can “become cruel.” So there’s also an event that will trigger – like Maria and Bruno, for example, who are in love when the game starts, if they’re both on your crew and Maria’s been killing people and gets the cruel trait, Bruno will pop up at an event and go, “Hmm, I’m a little worried, my girlfriend’s cruel.” She’ll go to the boss, like, “Can you do something about this? Can you talk to her or help her? I’m worried.”

Then there are three options. You can say, “Don’t worry, I’ll talk to her,” and she’ll lose the cruel trait, but she might lose some loyalty or morale, or might become sullen. Or, she might not, it kind of depends. Or you can basically tell Bruno to suck it up, she’s gonna be cruel, I prefer it that way, “You’ve got to deal with it.” Which, then, he will potentially get sullen. Or, if you, as a boss, are cruel, you can basically say, “Hey, if you want to be on my crew, you better be cruel, too.” Then there’s a chance he will gain that trait as well.

It’s all down to chance, though, and it’s up to the player how they want to handle that situation.

Can you outright lose a gangster for things like that, outside of death?

Katie Gardner: Yeah. There’s a small chance that like—well, Maria wouldn’t kill him, if that’s what you mean.

No, no, I meant like, would they just leave?

Katie Gardner: He might leave. There’s a low chance that if you pick a certain option, he’ll say “f—k this” and leave the gang.

Will he work for someone else?

Katie Gardner: Potentially! Which can cause all sorts of problems, if Maria gets into a fight with Bruno later on. She’s not going to want to kill him, but you can make them kill each other. There’s all kinds of craziness that can happen.

Brenda Romero: You wanted to know how deep it went, right?

Gangsters also have loyalty to you so, depending on how loyal they are, they won’t get flipped by the police or become a mole. They also have morale; some characters really like a lot of combat, and if you’re not in enough combat, they can become disappointed in you and leave. All gangsters have notoriety requirements as well, so the more notorious you become, the more likely they are to work with you. So, the super-badass contract killers, when you first start the game, they do not give a s—t about you, your crew, your plans; there’s not a chance you’re gonna work with them.

But there is an opportunity. When you’re on that crew screen you can see the connections between them. So if you can get somebody who’s really low-level who will work for you, given your notoriety, and you get that character’s loyalty up, there is a possibility they can eventually introduce you to that very high-level character, and you might get access to them. Crew management is super-important.

Interesting. I didn’t think it worked like that. When I was looking at that crew screen in the demo, my thought was, “Oh, if I eventually get that one, they’ll be powered up or have a bonus by being in the same crew together.” But I didn’t realize it worked the other way, that you could actually obtain them through those connections.

Brenda Romero: Also, during play, it’s quite possible that they can fall in love. They can have love triangles, people can get killed. This is not in the game anymore, but one of those “well, that’s a bug” moments. It’s just because we treat bosses pretty much like we treat everybody else, and there was even a point in time when gangsters could fall in love with a boss. I had two characters in love with me, which I thought was pretty cool, until jealousy erupted and one shot the other and killed him. So we took that out, because you don’t want – obviously, you as a boss are spending a load of time with the gangsters, and you can’t have your whole crew being like, “I love you.” That’s just weird and not really boss-like at all.

So, we decided, as the boss, you can love who you want to love. Like, whoever I’m playing loves Maria Rodriguez, and thinks she’s the best gangster in the game.

Katie Gardner: I thought you were going to tell the story about The Cleaner. One of the gangsters, his name is “The Cleaner,” and there was a bug with him where he would fall in love with himself. But then, he was also extremely jealous, so if somebody else fell in love with him, he would kill them, because he was the only one who was allowed to love himself.

Chris King: No truer form of love than to love yourself.

If you ally with a boss, do they leave their safehouse to go their brothel or casino? Do they provide opportunities for ambush aside from just attacking the safehouse?

Chris King: Not right now. It’s probably to avoid the problem of losing your safehouse and your primary base and the AI’s still around, making a “Schrödinger's Faction” at that point. It’s something a player could solve very easily, but it’s not something we wanted to push the AI into at the moment.

Brenda Romero: There are plenty of ways, though, to sabotage a boss. I love to form some kind of an alliance with somebody in the early game, and see if I can get them to take another boss out. I like to kneecap people early, especially playing a tight game like I do. Chris disagrees with this, because he feels like I’m giving different empires to other people, but then I’ll go pick them off. You can also poison their alcohol or try to start something between two other bosses and start a big war. There’s all kinds of things you can do to screw other people over.

As I’ve mentioned, I don’t really think there’s a game exactly like Empire of Sin. That being said, what might have been any game influences that fed into its development?

Brenda Romero: If you smashed several games together, the first layer of this cake would be Civilization. If I had a desert island game, it would be Civilization – Civ Rev, specifically, but I’ve played them all. So, wouldn’t it be cool if, instead of playing Napoleon and Gandhi, you could play Angelo Genna and Al Capone? So, that’s one. The other is the Jagged Alliance series. You’re forming a crew, and you’ve got to manage this crew to try to do your work for you, but they have their own agency, let’s say.

Chris, before coming to work with us, spent years at Paradox. He is a strategy game in human form. You can see those are the influences. Katie is the result of far too many internet crawls, far too much research. Four people are on the writing team, and we wanted to bring the game to life in a vibrant way.

I know there’s not a game like Empire of Sin, and that’s fantastic, because we made it, and we made it before somebody else did. But there’s also not a designer in this world who hasn’t said, “You know what, how did so-and-so solve this problem? How did they handle it?” We didn’t have that. So, we solved that problem with experimentation. We’re crazy proud of the game.

Katie Gardner: I play lots of RPGs, those are probably my favorite type of game. Branching dialogue and using skills in dialogue, giving the player choice in circumventing combat, or getting more money from somebody, or finding out stuff that maybe they’re not meant to know right away. The Fallout games would have been a huge influence, but there’s loads of other games like it.

Chris King: Inspiration for the strategy layer… I would say there’s no specific game that was inspiration for this, since there’s not a lot doing this kind of thing. It’s more the distilled experience of making strategy games, which has fed into the design process of the strategy layer. When you’re trying to set up strategy, you’re trying to set up rationales and reasons so that players can think about their choices.

You did say he’s a strategy game in human form.

Brenda Romero: You have no idea. Chris’s experience has been invaluable. We often describe the game as a “systems soup.” So, the ability to distill that, to help players figure out why they want to open a brothel versus a casino; because, as a player, we want you to be thinking about these decisions. Why would you want to become an ally of Salazar Reina vs Angelo Genna? It depends on who you are as a boss, it depends on who the other bosses are in the game. There are so many whys, and it’s such a big design.

There’s a lot of depth, and Chris became a puppetmaster pulling that all together.

Ian O’Neill: [For me,] every turn-based combat game in the last 20 years. There isn’t something or some remnant or some idea or shadow of something that I haven’t looked at or played that hasn’t influenced my combat designs in some way. The 800-pound gorilla in the room is XCOM, and it’s one of the influences. My own experience with turn-based combat goes back to the Megadrive, and the early Final Fantasy games, and I even have my Vita beside my bed simply because I play a game called Front Mission, particularly Front Mission 3, which is one of my most favorite games of all time.

The boss abilities and such are all me, though. They come from the boss’ lore, the characters, and their personalities. I knew Capone had to have a tommy gun and a submachinegun ability, but the question was how to dial that up and make that a boss ability.

So, you’ve really never done voicework before?

Ian O’Neill: This is also my first real official game as well. I’ve never designed anything to this scale before. This is my first spin.

Brenda Romero: [Ian said] “I don’t wanna do it, but I’ll do it because we need these lines.” Then he gets in the booth; getting him out of the booth was the problem. An absolute natural.

Ian O'Neill: Once I got over the initial fear, that first barrier, it was so much fun. It was just, to let loose with, “I’m Frankie Donovan, who the f--k are you?” That was totally adlibbed. That’s not written. That was literally, you know, the boss intro line.

I’m Irish—it obviously helps being Irish, it also helps having the gift of the gab—but it was one of those kinds of things where, I’m Frankie. What would Frankie say? He’s cocky and sarcastic… “I’m Frankie Donovan, who the f--k are you?”

https://ift.tt/355hkMQ

November 07, 2020 at 05:30AM